They later produced a sequel called Millennials Rising. Written in 2000, it’s attempting to describe exactly this generation, and it’s failing miserably in many respects, because they’re basically describing a successful, heroic generation, something which doesn’t ring true when you look at all those youngsters saddled with student debt, living with their parents and trying to find a job in a world with sky-high youth unemployment.

I’ve been trying to figure out what went wrong, and I think the basic problem was that the Baby Boomers started running countries much earlier than Howe and Strauss expected (from 1990 to 2010 in the UK and from 1993 to 2008 in the US, rather than the projected 2000-2020). The effect was that they treated 9/11 as if this was a big, once-in-a-century cataclysmic event (although it could — and perhaps should — have been treated simply as a horrible act of terrorism, rather than the beginning of World War III).

As a result, when the Great Recession hit us in 2008, we were already sick and tired of the “Bomb, bomb, bomb!” Baby Boomers, and we duly elected Generation X leaders — such as Obama and Cameron — instead.

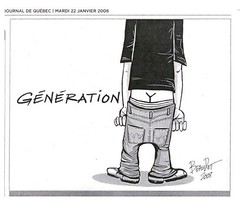

The result is drastic for Generation Y (called the Millennials by Howe and Strauss):

The Millennials’ Civic peer personality is not preordained. If the crisis comes too soon or (worse) unfolds badly, the Millennials will mirror the Progressives, a smart but hobbled generation that was later unable to realize the agenda of its Idealist elders. [p. 421]

Of course, the crisis didn’t really come too soon (unless one considers 9/11 to be the cyclic crisis called a turning by Howe and Strauss, rather than the Great Recession), but the fact that the Baby Boomers have been forced into retirement means that Generation Y cannot realise the agenda of the Boomers, so the effect is the same.

In effect, the Millennials are now a useless generation. Instead of being the willing soldiers for greying Baby Boomer leaders during the recession (and crises like Syria), they’re stuck with a frozen housing market (because Generation Y are risk-averse and won’t puncture the bubble), huge youth unemployment (which doesn’t bother Generation Y overly because most of us have got jobs and our kids aren’t looking for jobs yet) and many other problems.

Of course the Baby Boomers will eventually start dying off and vacating their expensive houses, but that could take another decade, and by then it could be too late for Generation Y. They will become the generation that never really got a good career and who never got to own their homes.

It’s good news, on the other hand, for the post-Y generation (let’s call them Generation Z). They were originally forecast to be a somewhat jaded generation, a bit like the generation preceding the Baby Boomers (the ones who were too young to fight in World War II but old enough to remember it), but now I predict they’ll be the new Baby Boomers: They’ll grow up with cheap houses and plenty of jobs, and with sharper elbows than Generation Y who thought participating was all that mattered. (As a parent, I’m already seeing signs that the schools are starting to toughen up a bit, but that’s perhaps better discussed in a separate blog post.)

Generation Y are starting to attract a lot of attention. Below, I’ve assembled some excerpts from various blog posts and newspapers articles.

Firstly, here are some comments from the London Evening Standard:

If you’re renting in Mile End, another surge in house prices is likely to fill you with despair, not elation. A teenager on a zero-hours contract in Enfield may wonder what he’s supposed to do with a 0.7 per cent rise in GDP, just as an unemployed history graduate in Woolwich will struggle to see how a new car plant in Solihull will help her job prospects. Meanwhile, a retiree in Richmond whose experiment with the buy-to-let market is paying off very nicely, thank you, may wonder what all this recession business is about.

To put it another way, any economic forecast is a generalisation that conceals huge inequalities and inequities. Generation Y (those born 1980-2000) have very good reason to feel that Osborne is describing a country to which they don’t belong.

After all, it is Britain’s young who are most likely to be trapped in the over-heated rental market, most likely to be on a zero-hours contract, most likely to use payday loan companies, most likely to have slaved under an unlawful “Workfare” scheme, and most likely to be unemployed even now.

According to the most recent statistics, there are 973,000 young people (16-24) still out of work. The figure rose by 15,000 in the last quarter, even as Osborne talks of a “game-changing” year for employment. And let’s not forget that four out of five jobs created during the Great Recession are in the lowest pay bracket. As the economy returns to “normal”, normal for this generation has shifted to something very different from their parents’ definition of the word.

The most striking shifts, however, are in attitudes. Iain Duncan Smith has persistently argued that this is an “X Factor generation” of “job-snobs” who believe that “success is not related to effort or work”. As Ed Howker and Shiv Malik note in their new edition of their book, The Jilted Generation, it seems that the young believe him. Surveys published this week show that Generation Y are more suspicious of welfare claimants than their parents — even though they are the most likely to be welfare claimants themselves. They are also more sympathetic to pensioners than to jobseekers — despite the fact that today’s pensioners are the richest ever to have lived.

The lessons Generation Y have drawn from the recession is that they are on their own. Their failures are their fault. Their successes need not be shared. Is this what Osborne had in mind all along?

Here’s an American commentator:

So what are millennials known for, so far? Well, to start with the obvious, we’re fucked financially. Anecdotes abound of millennials slaving away as unpaid interns and underpaid assistants, or slacking off as overqualified retail reps and baristas. “Generation Screwed,” Joel Kotkin called us in a thoroughly depressing July 2012 Newsweek feature that laid out the various headwinds holding us back: staggering levels of student debt (at least $25,000 on average, according to the latest reports); a 13.1 percent unemployment rate for 18- to 29-year-olds, compared to 7.9 percent nationally; and “a mountain of boomer- and senior-incurred debt … a toxic legacy handed over to offspring who will have to pay it off in at least three ways: through higher taxes, less infrastructure and social spending, and, fatefully, the prospect of painfully slow growth for the foreseeable future.”

And an article from the New York Times:

The millennials have developed a reputation for a certain materialism. In a Pew Research Center survey in which different generations were asked what made them unique, baby boomers responded with qualities like “work ethic”; millennials offered “clothes.” But, according to new data, even though the recession is over, this generation is not looking to gorge; instead, they are the kind of hungry that cannot stop thinking about food. “Call it materialism if you want,” said Neil Howe, an author of the 1991 book “Generations.” It seems more like financial melancholy. “They look at the house their parents live in and say, ‘I could work for 100 years and I couldn’t afford this place,’ ” Howe said. “If that doesn’t make you focus on money, what would? Millennials have a very conventional notion of the American dream — a spouse, a house, a kid — but it is not going to be easy for them to get those things.”

This condition is becoming particularly severe for the group that economists call younger millennials: the young adults who entered the job market in the wake of the recession, a period in which the unemployment rate among 20- to 24-year-olds reached 17 percent, when graduate school competition grew more fierce and credit standards tightened. Many also saw their parents struggle through a pay cut, a job loss or another economic disruption during the recession.

[…]

The millennials, in other polls, remain optimistic about their futures. Economists are less so. There is a persistent fear that they have entered a permanently lower earnings and savings trajectory. Even if the generation recovers, even if it ends up wealthier than the one before it, the scars will be deep and long-lasting. Kahn has started comparing recent graduates during the recent recession with recent graduates in the 1981-82 recession. She said the initial wage losses were comparable, and the trend looks set to repeat. “My inclination is pessimism,” Kahn said. “If anything, these guys might experience something worse.”

Other economists also envisioned a future in which millennials would spend less and save less. “I was talking with a mom who has a son in his mid-20s and told her the generation is not on the same wealth-building path,” said Signe-Mary McKernan, one of the authors of the Urban Institute study. “She had this look of terror on her face; our children are in trouble, and that’s such a worry for a parent. I told her, ‘Maybe this generation won’t have a worse life, but just a different life.’ ” And that may be true. Millennials are the best-educated generation ever. Their challenge may just be to preserve that advantage for their own children.

And finally:

Right now, most of the permanent underclass feels politically frozen: When one missed paycheck means descending into poverty without a safety net, unions and political activism seem like a low priority. Educated young people are frozen, too—caught in the privileged-poor paradox. Our meager (or nonexistent) paychecks incite righteous anger—especially when we think of our middle class parents’ luck at their age—but they also choke our very ability to organize, create, and take risks. As our wages fall, our degrees lose value, prices of food and rent rise, and workdays expand, we have less and less time to read a book, to join a rally in the next town over, to hop a bus to Washington, to even have a hours-long discussion about politics with our friends. Most Millennials aren’t starving, Great Depression-style, but they are starved for a low cost of living and a baseline of economic freedom.

It’ll be interesting to follow Generation Y over the next few years.